In our previous exploration of Concept-based Curriculum and Instruction (CBCI), we looked at the what, the why, and broadly the how of it. Now we are ready to peel back the layers of CBCI to further think about planning for it and the strategies that help create a concept-based classroom.

The Planning

When planning for concept-based learning and teaching, synergistic thinking is key. Synergistic thinking involves the symbiotic relationship between factual and conceptual thinking where students develop skills and process facts to a conceptual level. Learning experiences need to guide students to use the content and skills as vehicles to conceptual understandings that are transferable to new situations. Structuring learning so students can construct knowledge using an inquiry approach to learning sets up this synergistic interplay. Students can formulate their own questions to explore as they interact with the content in ways to actively construct meaning by making connections. To create the conditions of a constructive approach to learning for our classrooms, here are three possible steps to take when curriculum planning:

-

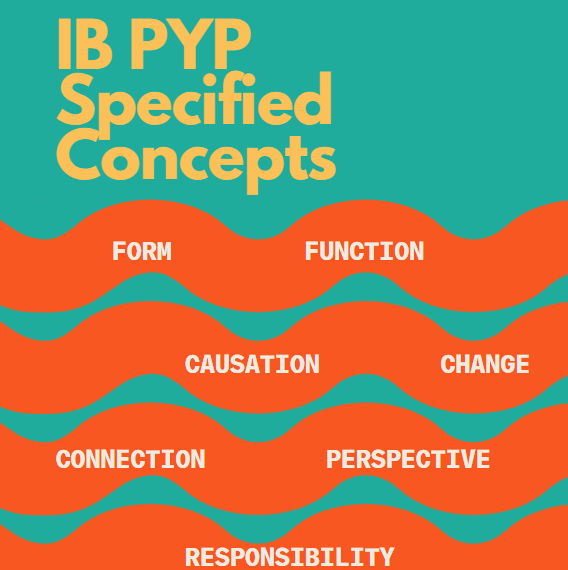

Begin with the end in mind by looking at the content in the standards so we can determine the concepts that we want to become those enduring understandings that are transferable.

-

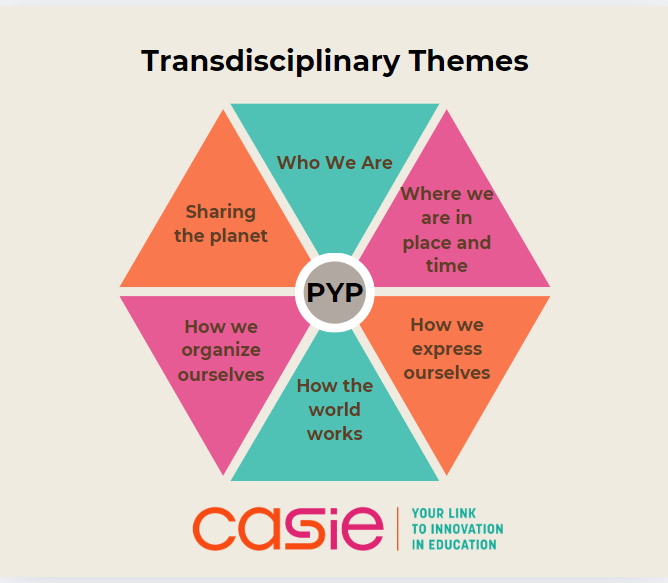

Create essential questions, central ideas, or statements of inquiry that incorporate the key and related concepts that are presented in a way that allows for and provokes students to be curious, question, debate, experiment, wonder, and explore.

-

Make the questions, thinking, and connections visible.

The Strategies

To plan activities that help students to think through topics, content, facts, and ideas well, we might consider the three steps listed in the above section. First, we can start with the end in mind by following the three-step process of Backwards Design introduced by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe in their book, Understanding by Design. The steps are: 1- Identify the desired results.; 2- Determine acceptable evidence.; and 3- Plan learning experiences and instruction. There are many frameworks and templates for using a backwards design for curriculum planning that your school may provide or that can be found easily if researched online.

Second, we can craft strong statements that capture the desired conceptual understanding. These statements should be judgment free, written in an active voice, using present tense, strong verbs, in third person, and with qualifiers so as to invite student exploration. This will equip students to better be able to make generalizations that are transferable. We want them to develop understandings about the topics and avoid giving the answers to memorize.

Third, activities that will help uncover thinking around the target information as well as prompt questions and wonderings are ideal. Structured routines that provoke thinking deeper and from various perspectives aid in the formation of theories and prod the debate and research into those theories. Revealing the thinking on paper through wall/chart displays, presentations, collaboration platforms, and through verbal exchanges all help to crystallize conceptual knowledge. There are a multitude of ideas for making thinking visible, including creating KWL/KWHLAQ charts, affinity mapping using sticky notes, Frayer Model, Project Zero Thinking Routines, online collaboration apps like Flip, Jamboard, Mural, Miro apps, and Padlets.

By looking at the curriculum demands in our own school, district, state, national, and global contexts, we can make the curriculum richer, challenging, relevant, and transferable by making it conceptual. Finding strategies that work for how we want students to learn can support the culture of thinking that we desire.

Author

-

Jill is the CASIE Director of Education. She has a Master’s degree in Educational Leadership from Clark Atlanta University and a Bachelor’s degree in Education from The Ohio State University. Her past work experience includes serving as a teacher, IB coordinator, assistant principal, associate principal, 12 years as a principal with the last 7 leading an IB World School, Executive Director of Academic Programs including all four IB Programmes, head of of Curriculum and Assessment for Marietta City Schools, and an IB Educator Network programme leader. She enjoys learning, reading, walking, spending time with her husband, daughter, son, daughter-in-law, and friends.

View all posts